Audio of the sermon is here:

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

Some people come to tell Jesus about a horrible thing that happened. Pilate—yes, that Pilate—was responsible for the deaths of some Galileans in the Temple. They were killed while they were offering their sacrifices, and so their blood got mixed with the blood of the animals they were offering. We don’t know exactly what happened or when, but somehow Pilate was responsible. These people were expecting some kind of response from Jesus, maybe to condemn Pilate, to empathize with those who were mourning, to lament their deaths, something. Whatever they were expecting, I can almost guarantee that it is not what Jesus says to them. I mean, what would you say if someone told you about something like this? You might say how horrible it was. You might say that the person responsible should have to pay. Something like that. Especially if it was something that someone had caused. But Jesus adds another layer: not only things that people do, but accidents. What about them?

Either way, most of us, most of the time, are not going to say what Jesus says: Do you think that these Galileans were worse sinners than all the other Galileans? No. If those who are telling Jesus about this are saying it because they are comparing themselves to those Galileans, they’re wrong. Do you think they were worse sinners than all the others because they suffered in this way? And Jesus puts it as an ongoing thing: those who suffered and continue to suffer; those who endured this thing and who continue to endure it. Jesus knows the suffering from that event didn’t stop when they died. Families and friends and communities continue suffering. Whether it was something that someone caused, like Pilate’s murder of those worshipers, or something accidental, like deaths from the collapse of the tower of Siloam, the grief goes on. No, it’s not that they got what they deserved, and the other Galileans, or the others in Jerusalem—or you—deserve better. You repent. Because there is no difference between one and another when it comes to sin. We confessed it today: I deserve punishment now and forever. Repent.

And repentance is not just confessing your sins. That’s a necessary part of it. Indeed, confess. But repentance has two parts: the confessing of the sins and the believing of God’s forgiveness in Christ. It is not just confessing, it is turning around and going the other direction. Repentance is to stop going in one direction, the broad road paved with sin and evil desires, that ends in death; stop going that way, and go the other way, which is the way of salvation and life. Repent, or you will also perish. No one deserves otherwise.

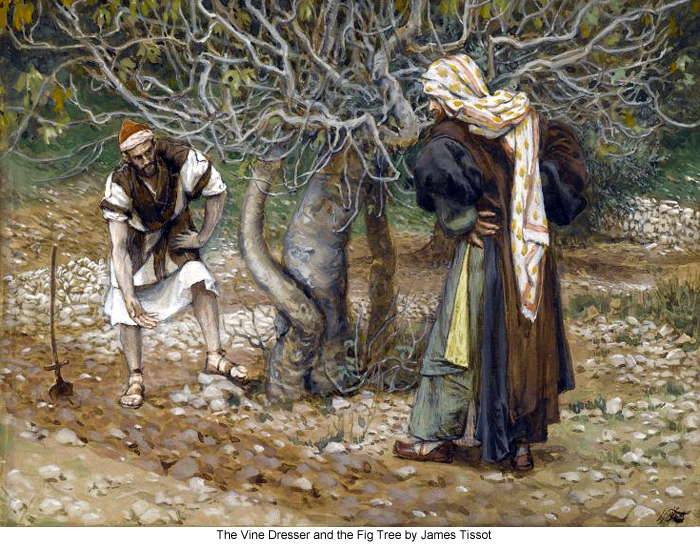

It might seem like Jesus switches tracks at this point, from words of repentance to an unrelated parable about a tree in a vineyard. But these are both about repentance. Where have we heard about trees and cutting and fruit before? All the way back at the beginning of the Gospel, John shows up preaching a baptism of repentance, that the Kingdom of God has come near. And what does he say? Produce fruit in keeping with repentance. The axe is already laid to the root of the trees, and every tree not producing good fruit will be cut down and thrown into the fire. Repent, or you will also perish.

But it goes further than that. There is a lot of talk about vineyards in the Bible. In the prophets, for example, Isaiah 5, there is a vineyard that God planted, and for which He did everything, but all He got was rotten, poisonous fruit. He says the vineyard is His people Israel. Jesus also tells parables about vineyards and seeking fruit, and about God receiving nothing but rebellion and death in return. Those parables that Jesus tells and the parables of the prophets are parables of judgment, of destruction, of exile; they are parables of sin and the need for repentance. The vineyard is the people of God, and this fig tree is among the people of God. This parable, too, is a parable of judgment. The owner of the vineyard has been looking for fruit for three years. If this follows Leviticus 19, the command given by God there was that a fruit tree in the land of promise had to be left alone for three years. In the fourth year also, no fruit could be taken because it was holy to Yahweh. Only in the fifth year could the people start eating fruit from that tree. If this follows that command, it means that the owner of the vineyard had been waiting for seven years to get fruit from this fig tree! Seven years of growth, seven years of work, seven years of waiting. And still, nothing. Cut it down! Why should it take up space, waste ground, waste resources. Fruitless trees should be exchanged for fruitful ones. Put the axe to the root, and burn the wood.

Maybe you’ve felt like that tree. You look, and you don’t find any fruit. You’re among God’s people, but you compare yourself to what you can see of others, and you’re not sure you belong. Maybe you should be excluded. Maybe God should exclude you. You keep trying, and all you see are more and more areas where you’re fruitless and faithless. But there’s no comparison here, no difference among any of us. No one deserves to be here, any more than anyone else. Naturally, of ourselves, we cannot turn ourselves around and produce repentance, faith, or fruit.

But then, like Jesus’ answer to those who tell Him about Pilate’s crime, this parable takes an entirely unexpected turn. Because everyone who was familiar with the Scriptures who heard this parable would have known that the proper outcome is the destruction of this tree. But then! The vine-dresser, the gardener, shows up in the middle of this judgment parable. In the middle of a parable about the need for repentance, the vinedresser puts Himself into the parable and intervenes with the Lord of the vineyard. “Lord, leave it. Let Me do My work, dig around it, put manure on it, and let’s see what happens in the days and weeks and months and years to come.” See, there is no fruitful vine. There is no fruitful tree. And so this vine-farmer comes and plants Himself right in front of the Lord of the vineyard, and binds Himself to this fruitless tree. He intervenes and intercedes. The vine-dresser is the Son, and He puts Himself not only into the parable, but into this whole fruitless world. He puts Himself in our midst, among us; He sees and knows you, and it’s not a mistake that He has chosen you. It’s not a fluke. He hasn’t mistaken you for some other, fruitful tree. He says, let me cultivate things. Let me do My work. Let me put manure on it.

At this point, I’m tempted to make all kinds of jokes about the way we use a synonym for manure, but let’s not miss the point: manure—whether the kind that comes from animals, or the green kind that is simply plants plowed under—is meant to fertilize, to put nutrients and minerals and other things into the soil for the sake of the plant. It gives things to the plant that it otherwise could not get. The plant doesn’t produce it. It can’t make it, or give it to itself. This is outside help, put on by a gardener-God. It is given by the Man who planted His crucifixion-tree in the barren landscape of a seemingly God-forsaken vineyard. He poured out His blood into the soil; He put His life into the ground. And when He was doing it, He said to His Father what He says here in the parable. It is almost word-for-word, because the word for “to leave” something is also translated elsewhere as “to forgive.” Here, the vinedresser says, “Lord, leave it.” On the cross, He says, “Father, leave them”—that is, “Father, forgive them.” Let Me do My work. Let Me give them the life they do not have in themselves. Let’s see what happens.

And the Father says, “Yes.” Yes, yes! Because this is the will of the Father and the will of the Son and the will of the Spirit, that you bear good fruit. So the Son binds you to Himself, wraps you up, and ties fruitless trees to His fruitful tree. Now, you grow with Him, you live with Him, you bear the fruit He gives. Apart from Me, He says, you can do nothing. No longer independent, individual, lonely, fruitless trees. Now He is the Vine and you are the branches. His life is now your life, because He took your fruitless death and died it first. And just as God built His vineyard again around His Son, just as He kept His promise to Israel and gave them a vinedresser, so He will keep His promise to you, that you are His own precious planting. His Son is continuing to do His work, continues to intercede for you! The worst sin is not whatever one you chose to do, or whatever you think you’d like to do. The worst sin is despair: to try to escape the careful gardening of the Son of God, to go away from Him, from His Word, from His bodily and bloody life; to untie yourself from His cross and die your own death. No, dear ones, do not despair of the mercy of the holy vinedresser. He has turned your wayward roots and branches away from your own path of death and destruction, and turned you toward His life and salvation. And He is faithful; He will do it. God will bring to completion the work He began in you at your baptism, and He will do it until the day of Jesus Christ.

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen. “And the peace of God, which surpasses all understanding, will guard your hearts and your minds in Christ Jesus” (Philippians 4:7, ESV). Amen.

– Pr. Timothy Winterstein, 3/21/25